Somnai: Immersive Theatre Security Vulnerability

Immersive Theatre Meets Technology

I love immersive theatre and I work in VR Game Development. So when an immersive theatre production using VR arrived in London, I had to go check it out!

Somnai is an immersive theatre event by Ellipsis Entertainment (dotdot). You are led through a series of rooms containing a mix of VR experiences (using Oculus Rift headsets) and some theatrical scenes.

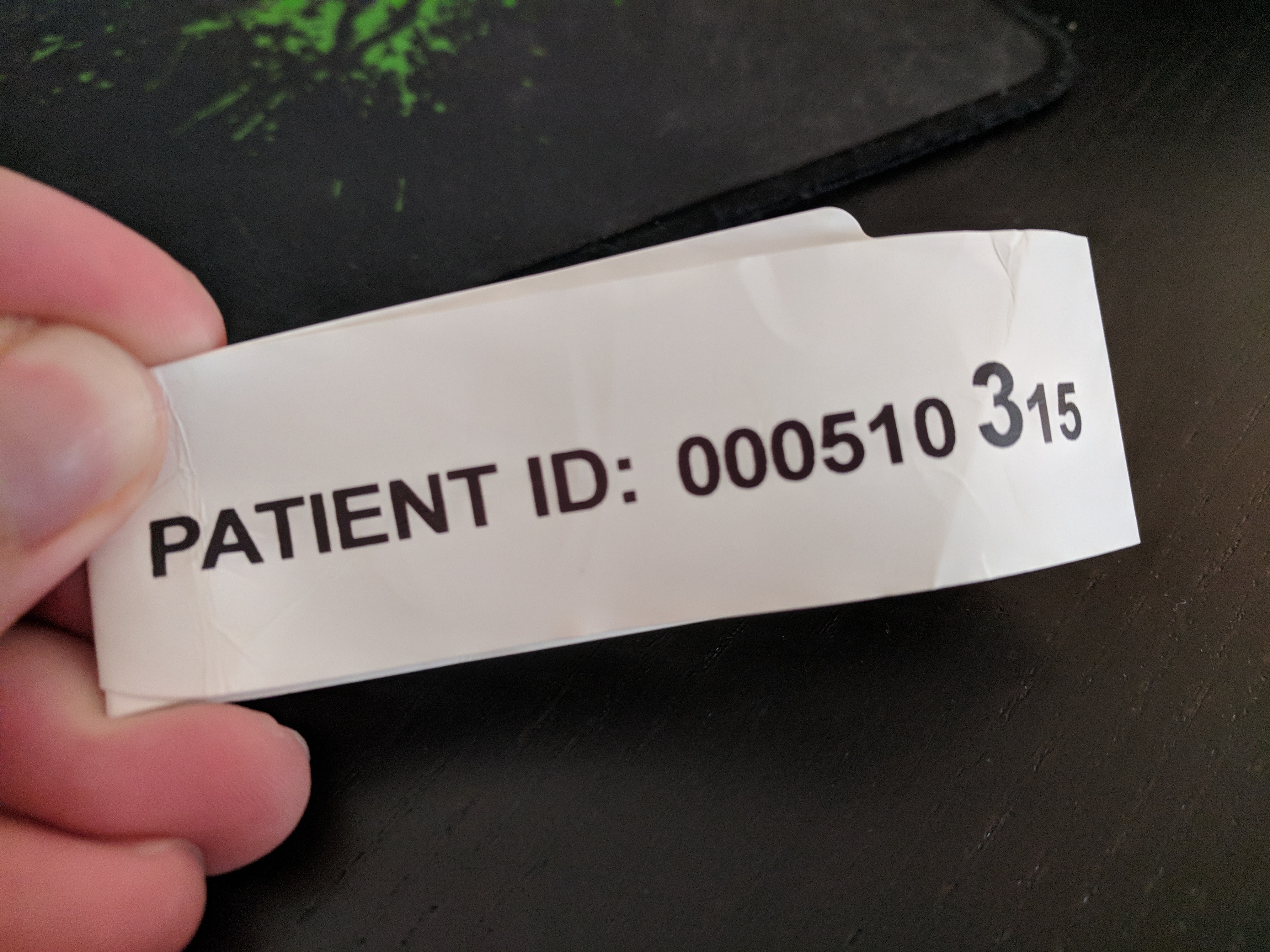

At the start of the experience, you are given a wrist band with your Patient ID on and a FitBit. Here is my wrist band:

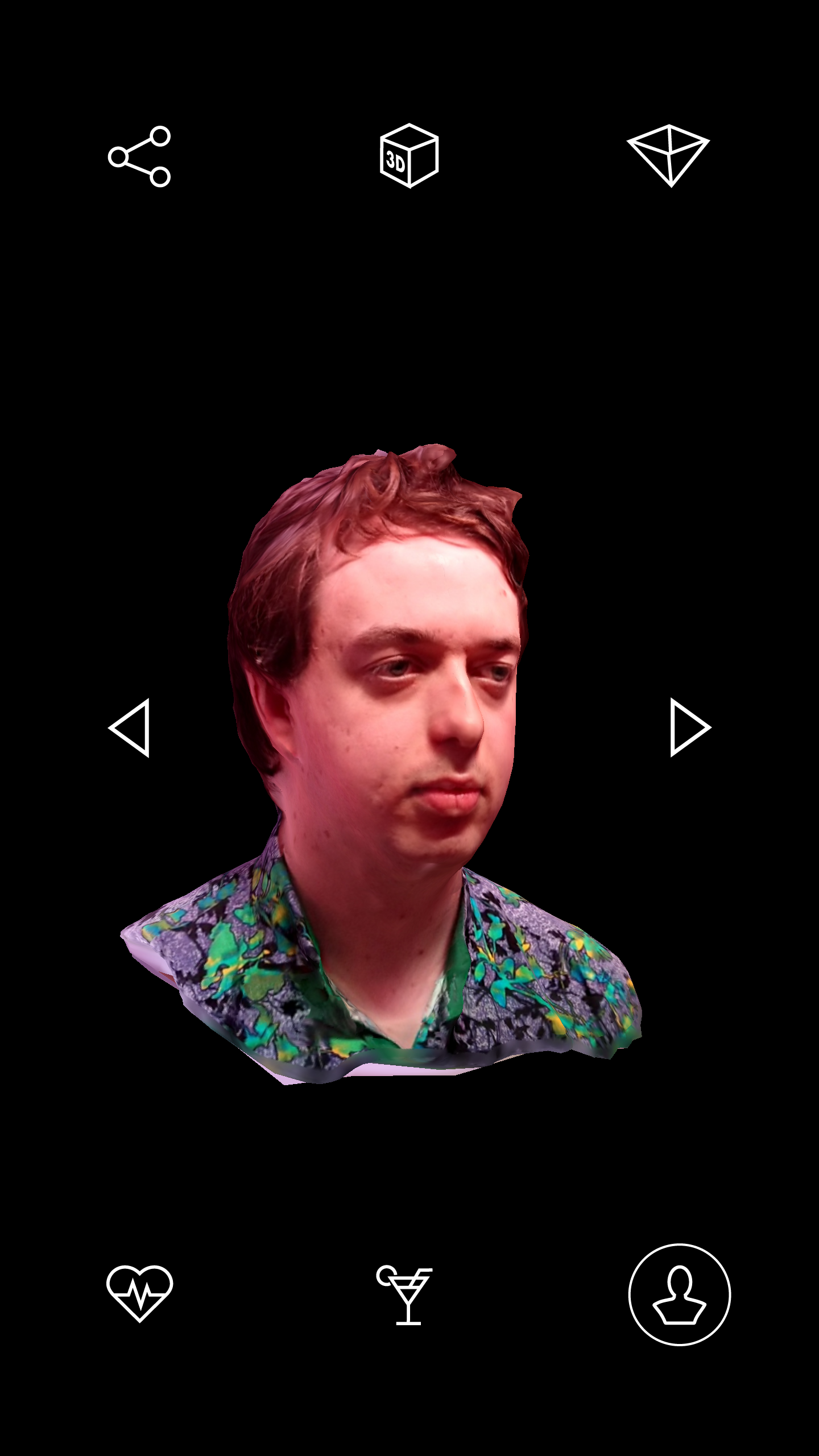

At the end of the experience, you can download a mobile app. If you enter your Patient ID into this app, you can see a 3D scan of your own head and a graph showing you your heart-rate throughout the experience.

That's pretty cool! A 3D model of my own (slightly angular) head is a novelty, and works well as a little souvenir I can show people when talking about my experience. The heart-rate graph is also an interesting bit of data, telling me how my heart-rate was throughout the experience.

Traffic Intercepting

Obviously, I want to download the raw 3D model file of my face from this app. I want to knock up game prototypes with my giant face for terrifying placeholder boss fights or something. Luckily I have a phone rigged up with a custom cut of Android and my own SSL certificate so I can observe what apps are up to regarding their network traffic.

Let's boot up the app and enter my patient ID to see what the app does! I am using Charles Proxy here to intercept my phone's traffic.

... Um... the app isn't requesting any data? That's weird. Charles Proxy is void of seeing any network traffic from my phone, but somehow it still managed to download my 3D head model!

No HTTP(S) traffic found, let's try something else...

Let's grab the APK and see what's going on under-the-hood. You can download APKs directly for apps easily by transferring from the phone itself, or a website like APKPure

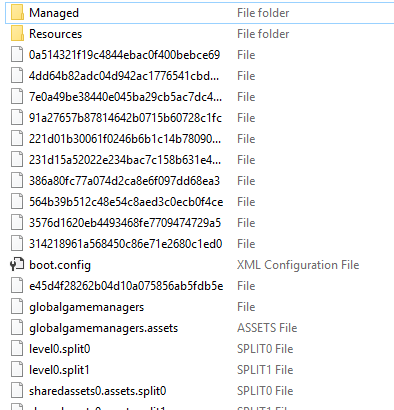

APKs are actually zip files, so a quick rename and a browse through reveals this Data directory.

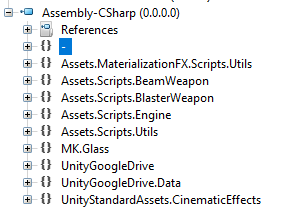

Aha! I recognise this folder layout, this is a Unity app! Unity uses C# DLLs for it's code, which are handily kept inside that Managed directory seen above. I use ILSpy, a free open-source .NET decompiler which will show (roughly) the original C# code from a given DLL. https://github.com/icsharpcode/ILSpy

The DLL we're interested in is Assembly-CSharp.dll. This file contains the main game code for a Unity project. The other DLLs are usually the core Unity libraries, and any plugins the developer is using. Let's open this up in ILSpy and take a look.

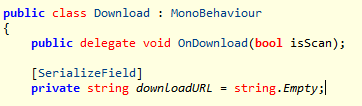

After a quick scan through the classes, we can see this Download class.

Sadly the downloadURL property doesn't look like it's defined in code. Analysing any references to the downloadURL variable doesn't reveal any part of the codebase setting this variable to any meaningful value. This likely means the downloadURL variable is being set somewhere inside the Unity scene file. When you make a Unity app, Unity makes up binary files containing the scene data (containing information about exists in your map), which end up as level files in the packaged game. While there are tools out there which can extract and parse the binary level data in a human-readable form, I am going to try hunting through the binary data myself first. I spotted a level0.split0 and level0.split1 earlier, suggesting this Unity app is made up of a single scene, which should be easy to hunt through.

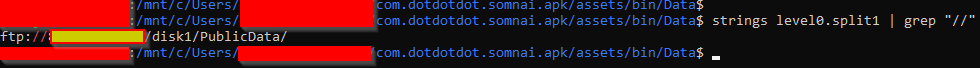

Using some unix tools, I can extract data from binary files. Running the following will extract readable strings from the level0.split1 binary file, then search for any lines containing "//", which hopefully will give me a URL or some sort.

Boom! First attempt and we have a URL! I have obscured the address here, but if you look closely, you'll notice it's actually an FTP URL! That's why Charles wouldn't pick it up, as this is very out of left-field! Generally you don't find proxy applications supporting FTP, as FTP isn't really intended for web applications such as this.

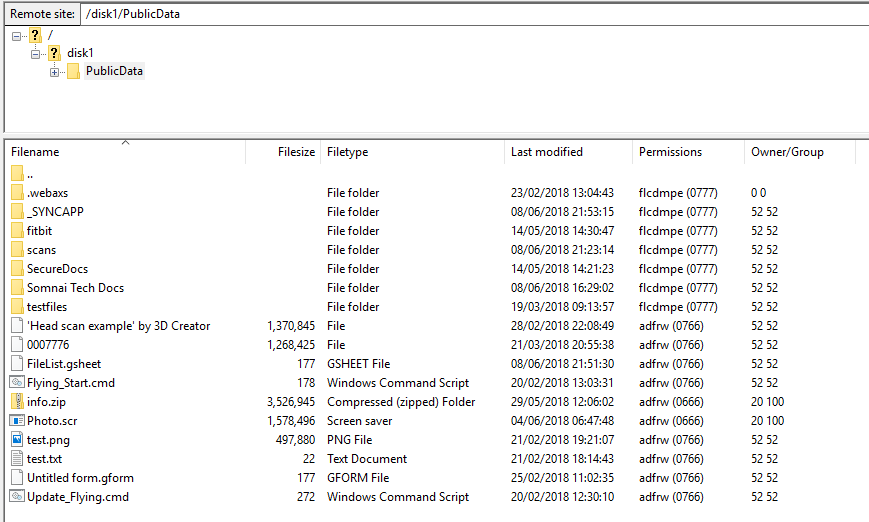

Based on the code we found earlier, we cannot see any evidence of authentication, so I suspect this is an unauthenticated FTP server. Let's see what else we can find by booting this up in FileZilla without any username or password.

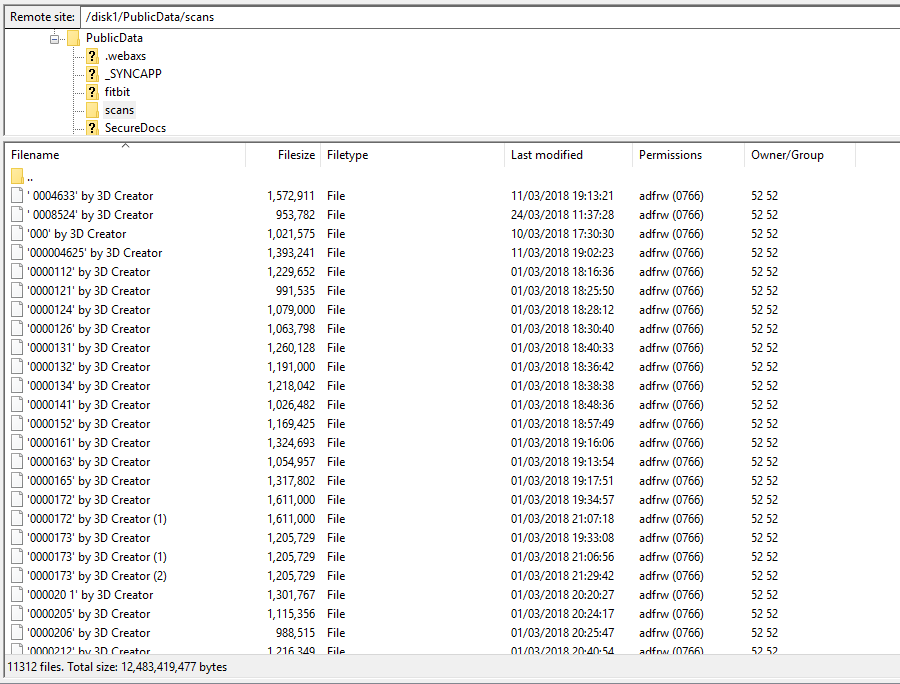

Hurrah! I can see where all the scans are kept and download my face! I can also view every face scan of every other audience member who has visited Somnai throughout the production run.

Let's have a look at that scans folder.

11,312 head shots! This is a fascinating data set. If I didn't care for these people's privacy I would immediately build a model of the average head of a London immersive theatre audience member.

Interestingly, when the app downloads the head scan, the filename must match a very specific naming convention. Throughout the folder are numerous typos, meaning a lot of audience members can't ever download their headshot because their ID won't match up correctly (or they could just anonymously login to this FTP server and hunt for it themselves I guess).

The head model file should be a 7 digit number. However there are lots of examples of things like:

- '0000172' by 3D Creator

- 0000232 (1)

- 696'Untitled' by 3D Creator

- 476511_

None of these will work in the app, as they are not valid patient ID numbers, which is a shame, as at £35 each, the 3D head scan is one of the few interesting aspects of the experience.

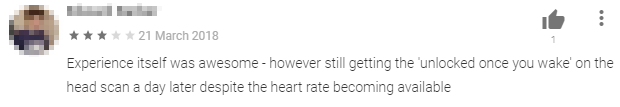

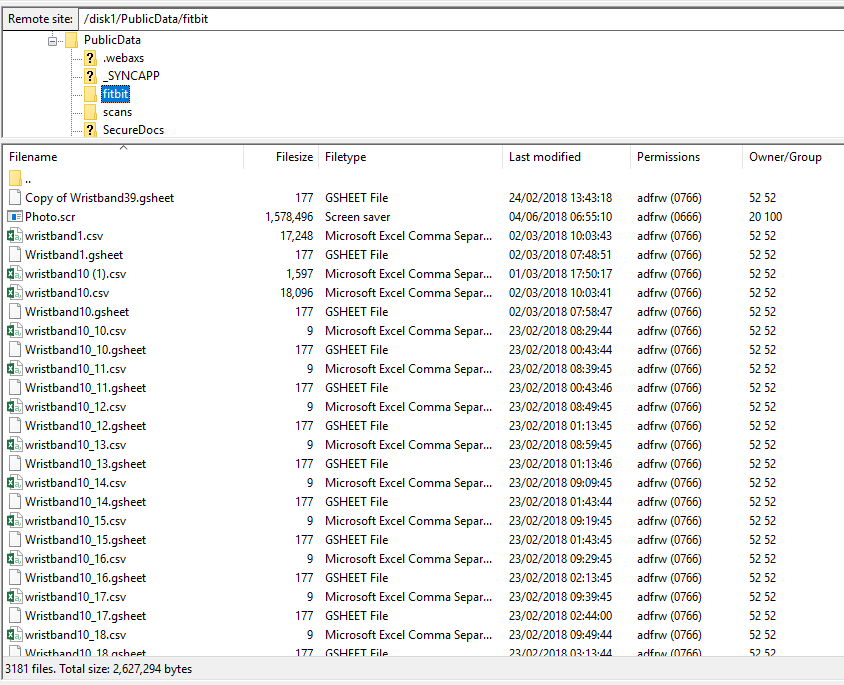

Looking at some of the Google Play reviews, this seems to be a common problem where people have never been able to get their face scans due to staff incorrectly naming the files.

Just like real life, I wore this FitBit for nothing

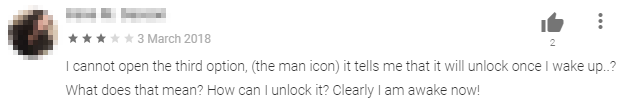

Let's also have a look at the fitbit folder.

3181 files... odd. For some reason there are significantly less fitbit data files than headshots? Why is that?

Turns out, there are actually only a small selection of heart-rate samples accessible. When you enter your patient ID, the app will take the last few digits of your ID and fetch the matching heart-rate graph from the FTP.

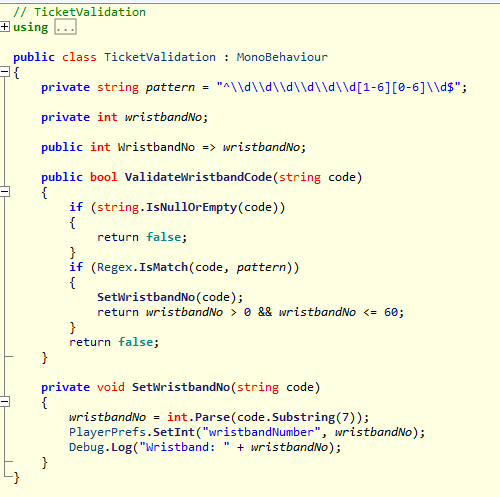

Let's look at the app's code for validating your wrist band ID.

As you can see from the code, the variable wristbandNo is based on the last two digits of the wristband ID (mine is 15). There is also some validation here, confirming that the ID must be between 1 and 60. This number is used later to download the heart-rate graph using this URL pattern:

ftp://[SITE ADDRESS]/disk1/PublicData/fitbit/wristband[WRISTBAND ID].csv

My band ends with the digits "15", so my heart-rate graph wristband15.csv. Because the ID must be between 1 and 60, there are only actually 60 possible heart-rate graphs available.

As you can see above, these CSV files also haven't changed since February (it's now June), so the whole time users are wearing FitBits, they're not actually being recorded at all. This is a shame, as this was made out to be quite a big deal during the experience, and explains why when looking at my heart-beat graph after the show, it didn't match how I believed the experience played out at all.

Assign the Write Permissions

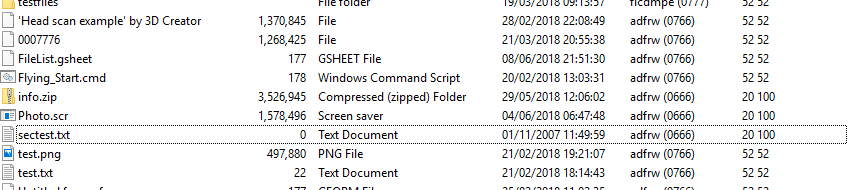

Eagle-eyed readers will have already spotted some interesting settings in the Permissions column in the above screenshot. 0766 means that all users in the system can read and write files... so can I write files here too?... Let's try.

Let's create a quick test file. I've made an empty text file called "sectest.txt" and try uploading it with FileZilla.

And there it is. The server is completely writable anonymously. Not sure why the file has a timestamp of 2007, but I will assume maybe an unusually configured FTP server?

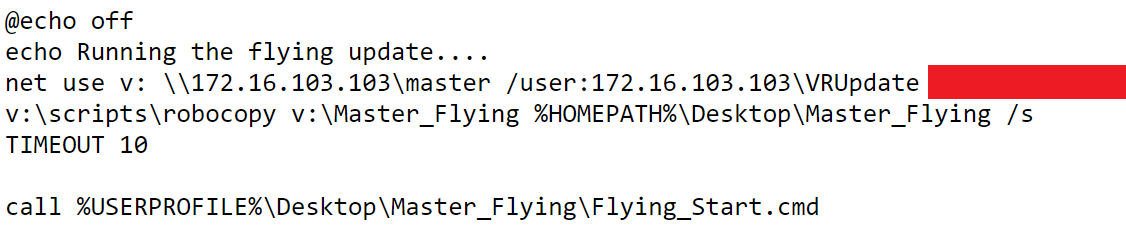

Not only are the 3D models available for me to write over, but some update scripts too:

This script has hard-coded credentials to connect to a network drive and copy VR builds to the local machine. It wouldn't take any effort to overwrite this script so that it performs additional malicious actions.

Viruses Everywhere

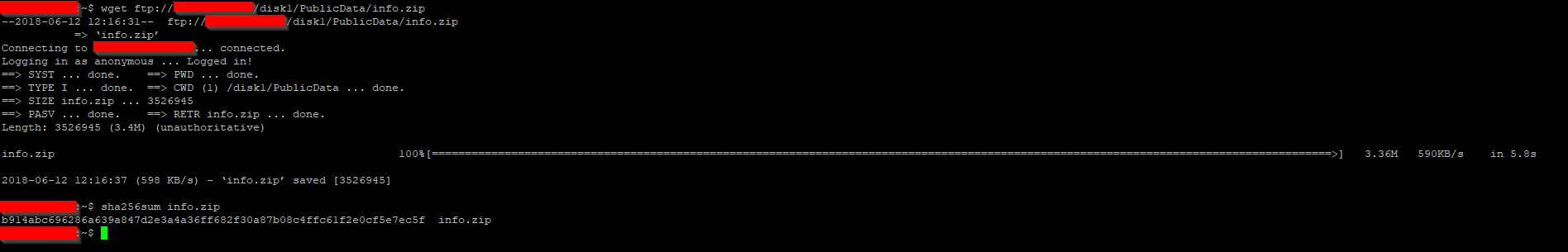

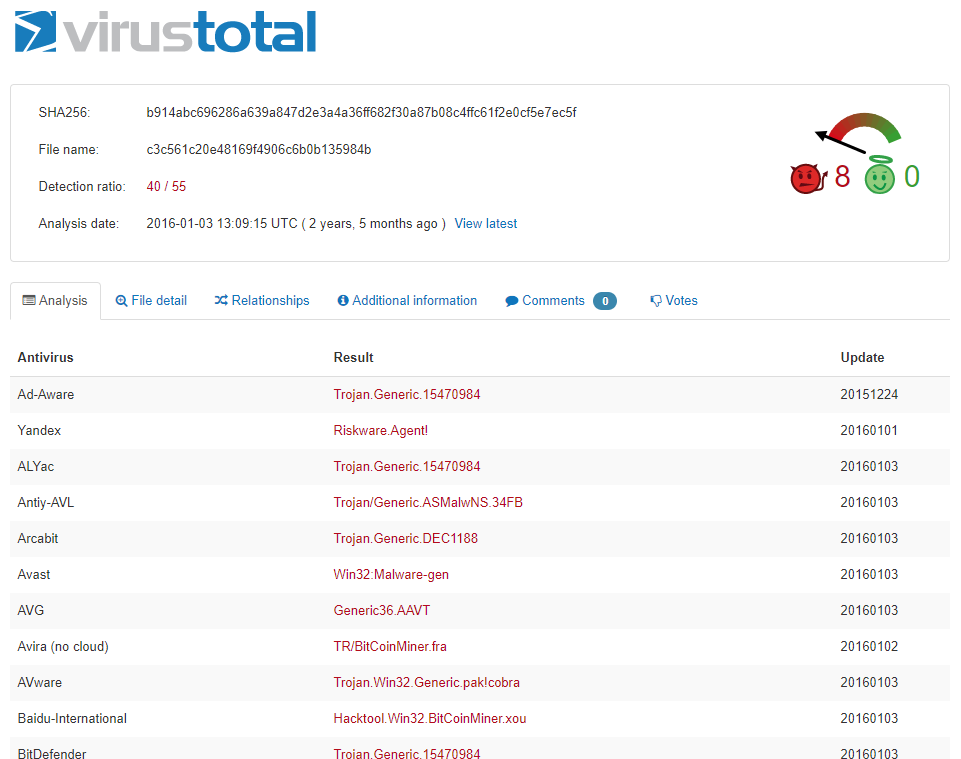

Every single folder on the serer has two identical files info.zip and Photo.scr. This was a little peculiar, so I downloaded one of the zip files and checked it against the virustotal.com site.

The above command shows me that the SHA hash for the info.zip file is b914abc6[...]. A quick search of VirusTotal confirms that this file is definitely dodgy. I'm using a SHA hash here to avoid ever actually touching the file myself, just to be safe :)

See full virus scan results on VirusTotal

Easily Prevented

What is interesting about the viruses uploaded, as well as my test file, is that they have different permissions settings when uploaded through FTP to all the other files on the server. This confirms that these viruses were uploaded by malicious users (likely automated scripts) on the internet looking for open FTP servers to host viruses from).

What does this mean and why is this important? It means all the 3D head models, all the FitBit data, and all the private files stored here - none of these are uploaded via the FTP server. All these files must have been uploaded through some other means in order to get these different file permissions. So, there is absolutely no reason for this server to be allowing write access, since all the internal data available is written via some other means.

Timeline

(bold - responses from dotdot)

- March 18th 2018: Initial Disclosure to [email protected]

- March 19th 2018: Response from dotdot

- March 24th 2018: Reply back to dotdot with additional information and suggested disclosure date of 18th May 2018

- June 11th 2018: Further email to dotdot (after receiving no reply for 85 days) with new suggested disclosure date of 18th June 2018

- June 13th 2018: Further email to dotdot with draft of blog post

- June 15th 2018: Response from dotdot, says FTP server has been taken offline until internal capabilities allow them to fix it (I should have checked this)

- June 16th 2018: Reply back to dotdot with some solution suggestions

- June 18th 2018: Reply to dotdot stating FTP server is still running and vulnerable - decided to delay disclosure a few days

- June 20th 2018: Public disclosure

- July 21st 2018: Service still vulnerable and accepting public uploads